2 principles to find viral content

|

Hello and welcome back. Last week I shared the strange experience of going viral. (If you’re new to the list, here’s what happened: A video I shared got two likes. One from Jack Dorsey, the founder of Twitter. The other came from Elon Musk.) 4.8 million views later, I’d like to share with you how I found it.

That story comes down to two factors.. 1. The Mentality of a CollectorI come from a family of collectors. (The boundary between a collector and a hoarder is often hazy.) My grandmother collected antiques: porcelain boxes, pewter mugs, Chippendale highboys. My father collects instruments: guitars, ukuleles, banjos. Unless you’re rich, the art of collecting is discovery and valuation. You find sources that are neglected by the market. Flea markets. Garage sales. Facebook “free stuff” groups. You rummage through cardboard boxes. You get dusty. You explore with a strategy of serendipity. In time you hone your eye to identify the buried treasure. With luck, and attention, you may find a Ding bowl. With content, it’s the same. Ask yourself: What sources are people neglecting? Where is the hidden value? How would this shine in a different setting? 2. The Human SignalThe surest sign that something has value to people is that it is exchanged. (Take those paper bills printed with presidents' pictures on them, for example...) That’s why I always pay attention to what people share with me. When a reader sends something, I know he believes it has value. So here’s the story…About a week ago, a reader shared a link in response to something I wrote. The link led to a 2-year-old article on the Intellectual Dark Web in a small, intellectual cultural journal. In the fourth paragraph, the author mentioned Marshall McLuhan's theory that weak identities lead to violence as people feel the need to prove they exist. He linked to a video. I opened it and was immediately fascinated. A few minutes in, when the interviewer asked McLuhan about the FBI and CIA, I leaned in. (I've been covering the history of entanglement of intelligence and media.)

When McLuhan went on his riff about "discarnate identities" on TV (and the Internet), I knew I had found something. A $3 million Ding bowl? No. But something of interest to people—as it turned out, millions of them. This wasn't a fluke. The same thing happened a few months ago when a reader shared with me a video of Yuri Bezmenov, a Soviet defector. I dug a little deeper, and this happened.

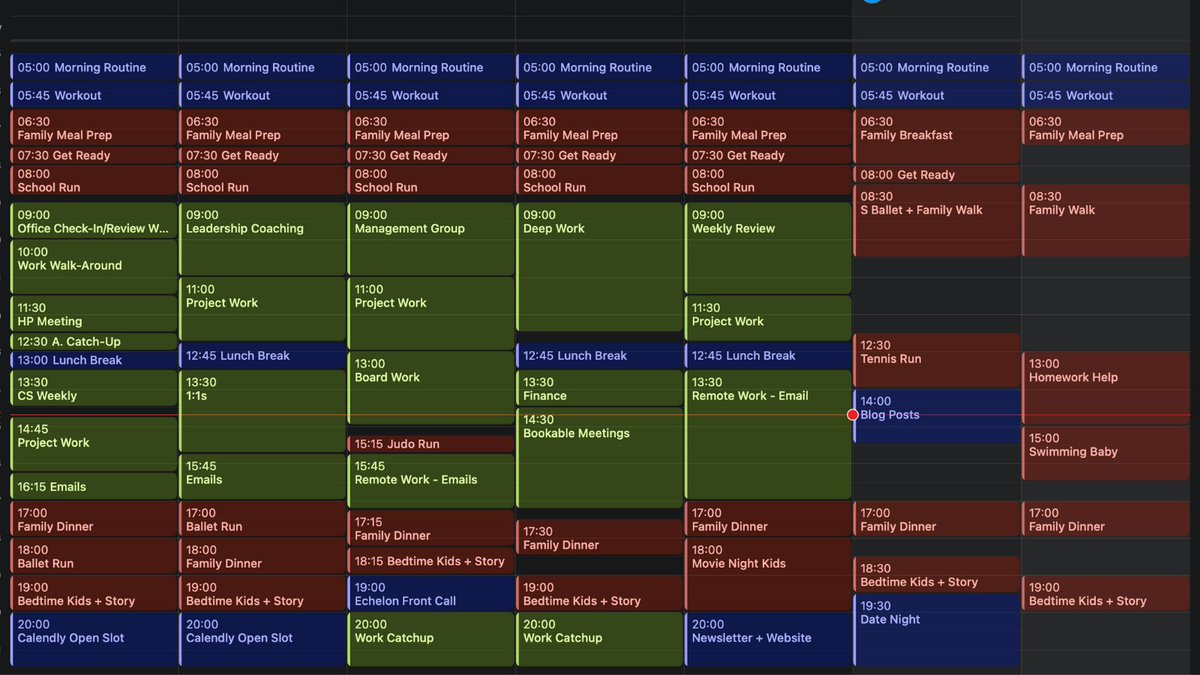

The moral of the storyIf you want to bring ideas of surprising value to people, pay attention to what is being exchanged within your audience...and peel back one one layer more. Often the best content comes from taking from what's in plain sight and putting it in a new light. One Last Thing: What I'm EnjoyingTobi Emonts-Holley is a CEO and a father of six. He also exercises daily.. As the father of infant twins and a three-year-old, I'm in awe of anyone who can juggle twice that number of children. Check out his calendar below. He wakes before 5 every morning. As I said: awe:

What's on your mind this week? Let me know if there's anything you'd like to explore. I'll be digging further into how the media works — and my experience of it—in the coming weeks. Until then, thanks for reading, Ben |

|

Benjamin Carlson

I'm a communications exec and a former editor at The Atlantic and foreign correspondent. Subscribe for lessons from my 15 years in media and PR

Thought Leadership Lessons from the Greatest Logo Designer of All Time Over the last two years, I’ve traveled through a succession of university archives—aesthetically gorgeous and teeming with deep insights—where I studied the papers of twentieth century visionaries, innovators, and creators. One of them was Paul Rand (1914-1996), a giant of twentieth century graphic design, whose papers are housed at Yale University. Rand was the preeminent logo designer of his day. He created the iconic...

Content Lab: How to Be Positioned Right in 2025 This Jaguar ad is an accidental masterclass in what's changing in the culture and where it's going, right beneath our feet. What might have seemed provocative a year ago now feels utterly tone deaf. What was intended to appear bold, futuristic, and enlightened instead seems flat, cowardly, and anti-human. Consider for a moment. It has no human voices. No smiles. No emotions. No sense of place or time. No melodies. No cities. No food. No roads....

The Carlson Letter Castor and Pollution, Max Ernst, 1923 Do you like your online self? Do you know your online self? Whether you like it or not, one of the first things a new acquaintance will do is Google you. What do they see? If you’re like many of us, they may see a series of results offering to sell your address, phone number, and possible family affiliations. Then they may see a Facebook page (yours, or maybe a namesake’s), your old work headshot, your LinkedIn profile. If you have a...